Key Takeaways:

- Elvis Presley’s longtime manager was Colonel Tom Parker, who helped the rock ’n’ roll singer build his massively successful career.

- For all the highs of their partnership, Presley and Parker abruptly parted ways in 1973 after Elvis delivered a profanity-laced tirade onstage.

- The musician and manager soon reunited, but their partnership, hampered by substance abuse and gambling, was never the same.

In March 1956, Colonel Tom Parker took over sole management of budding star Elvis Presley, beginning one of the most famous—or infamous, depending on your perspective—partnerships in music history. Almost 70 years later, a new book is lifting the curtain on their highs and lows, including one memorable spat that altered the pair’s friendship forever.

Veteran Elvis biographer Peter Guralnick examines the life and legacy of Parker—from his childhood in the Netherlands to his two-decade tenure as Presley’s right hand man—in The Colonel and the King. The book includes dozens of Parker’s personal letters to Presley and other confidantes, offering a never-before-seen look at the manager’s bond with the singer.

The Colonel and the King counters the enduring perception that Parker, who lied about his origins and maintained an eccentric public persona, was an overbearing force who stifled Presley as an artist. “He completely removed himself from Elvis’ creative life,” Guralnick recently told The Los Angeles Times. “It was a partnership of equals, but Parker didn’t get involved in that aspect of Elvis’ career.”

Still, although Elvis once said he loved Parker “like a father,” the pair certainly had their share of disagreements. In fact, the pair’s relationship nearly ended for good in September 1973 after a late-night concert gone wrong.

Elvis and Parker fired each other after a concert outburst

With his movie star days behind him, Presley hoped Las Vegas could revitalize his career. In July 1969, he played his first concert at the Westgate Las Vegas Resort & Casino, kicking off a residency that continued off and on for the next seven years.

But on September 3, 1973, Presley delivered a profanity-laced tirade during the final concert of his four-week run at the venue, which had changed its name to the Las Vegas Hilton, to put the arrangement in jeopardy.

According to Guralnick, hotel management allegedly intended to fire Presley’s favorite waiter, angering the singer. During a special 3 a.m. concert to commemorate his last night on stage, Elvis began berating Hilton company director and CEO Barron Hilton and replaced the lyrics to his popular song “Love Me Tender” with various obscenities. “To hell with the whole Hilton Hotel, and screw the showroom, too,” he crooned.

The outburst understandably appalled Parker, who was seated in the front row with Loanne Miller, his future second wife. He confronted Presley after the concert and wrote a letter to the singer later that day.

“We are not judge and jury, but performers, and have a job to do on that stage without getting involved with hotel employees during the performance,” Parker wrote. “I am not aware of the reason for your outburst in this matter, but I am sure you know why you did it, and it has not made things easy to patch up.”

Early on the morning of September 5, Elvis and his father, Vernon Presley, determined The King and the Colonel should go separate ways. Parker immediately tended his resignation letter in response. “With all the other incidents involved, this is the best solution for all concerned. I have no ill feelings—but I am also not a puppet on a string,” Parker wrote to Elvis.

One of the biggest partnerships in music was, seemingly, over. But Parker’s letter wasn’t the last word.

Elvis’ personal life began collapsing, too

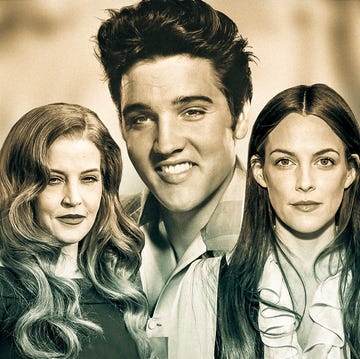

On top of his suddenly uncertain music prospects, Presley quickly experienced two major setbacks in his personal life that fall. The first was his divorce from Priscilla Presley, which was finalized on October 9, 1973. Still, the pair shared custody of their only daughter, Lisa Marie Presley, and remained on amicable terms.

More alarmingly, Elvis’ substance abuse landed him in the hospital. According to Guralnick, he was admitted to Baptist Memorial Hospital in Memphis for two weeks because of an addiction to Demerol, an opioid pain medication.

During this time, Parker had no direct contact with Presley and only heard through sources that the singer was in exploring the idea of another manager. But as Christmas approached, there were signs the tension had dwindled in Presley’s camp. Namely, Parker received brief telephone calls from both Vernon and Elvis’s bodyguard Sonny West. Maybe the partnership could be saved after all.

Elvis and Parker reunited but weren’t the same

Soon enough, Presley called Parker himself. According to the Colonel, the first question the singer asked was: “When are we going on tour?”

“I told him I could not answer that since he had never replied after he told me that he wanted to make a fair settlement [for the dissolution of their contract in September],” Parker later recalled. “‘Well,’ he said, ‘I want to start working.’”

So they did. With Parker’s help, Elvis continued touring and salvaged his Hilton residency despite his public blowout. He went on to perform an estimated 636 sold-out shows there by the end of his run in 1976.

However, his working relationship with Parker was vastly different after their reunion. As Guralnick wrote, the pair played a “small-bore game of retribution and retaliation.” An example of these small slights involved Presley making the Colonel wait on the airplane tarmac in bad weather before making their way to the next tour destination.

When Parker questioned the musician about his drug use or a bad performance, Presley often gave the same dismissive answer: “I know what I’m doing.” As Elvis’s health declined, Parker’s gambling habit spiraled downward, too. The manager sometimes spent 24 hours at the casino, and one session lasted at least two consecutive days.

The end of their partnership was seemingly near—one way or another.

Presley’s death devastated Parker

By July 1976, Presley’s condition backstage at a Hartford, Connecticut, concert brought Parker to tears. “The real Elvis is sharp and clever, but the person I saw tonight didn’t even recognize me,” he said. “No one knows how much I miss the real Elvis. If only I knew how to bring him back. I miss my friend so much.”

Presley’s health never improved and he died of heart failure in Memphis on August 16, 1977. Parker—who was in Portland, Maine, to prepare for an upcoming tour—flew back to Tennessee the following day with Miller and crew members. He ordered everyone on the plane to refrain from “emotional outbursts of any kind,” but his grim expression hinted at inner turmoil.

“I think Colonel spoke these words as much for himself as for the rest of us,” Miller said. “I believe he felt that if he allowed himself even a little emotion, he would lose control of his emotions entirely.”

Parker’s public perception is complex

After Presley’s death, Parker made multiple business arrangements to protect the Elvis trademark and handle publishing royalties from any new projects. His handling of The King’s affairs came under scrutiny, though, when lawyer Blanchard Tual, later appointed an ad litem guardian for Lisa Marie, determined Parker’s cut of roughly half of Presley’s earnings was exorbitant for industry standards. In 1982, the Presley estate sued Parker for contract manipulations and exploitation for personal gain. The two sides reached an out-of-court settlement the next year.

According to Guralnick, Parker actively preserved Elvis’s legacy in the following years. He organized an Elvis fan festival at the Las Vegas Hilton in 1987, enlisting Presley’s friend Wayne Newton as a headline performer. Parker was also invited to a special Graceland event commemorating what would have been Elvis’s 53rd birthday in January 1988.

Still, Parker, who died in January 1997 at age 87, has developed a duplicitous reputation for his alleged exploitation of Presley. Even the most recent interpretations of Parker, including Tom Hanks’s portrayal in the 2022 biopic Elvis, have seemingly painted him in a more villainous light.

But in telling Parker’s story, Guralnick hoped to illustrate the real truth lies somewhere in the middle. “I came to see the relationship between Parker and Elvis as a kind of shared tragedy,” Guralnick told The Guardian. “Each had their own addictions. [Parker] was somebody who was so vulnerable, not just at the time but vulnerable from his childhood in ways we simply will never know, suffering from some form of trauma, being somebody who really couldn’t stand to be touched by somebody that he didn’t know.”

Tyler Piccotti joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor and is now the News and Culture Editor. He previously worked as a reporter and copy editor for a daily newspaper recognized by the Associated Press Sports Editors. In his current role, he shares the true stories behind your favorite movies and TV shows and profiles rising musicians, actors, and athletes. When he's not working, you can find him at the nearest amusement park or movie theater and cheering on his favorite teams.