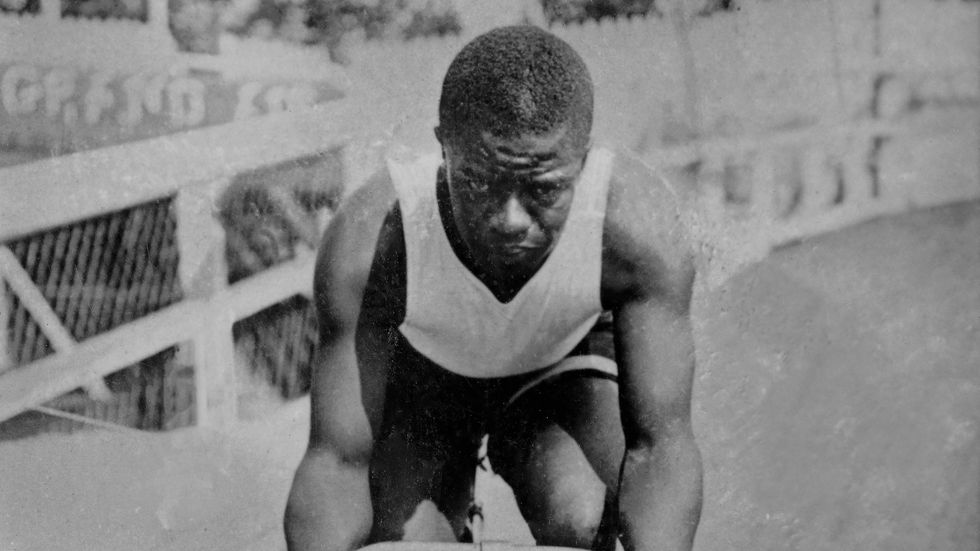

Most people know the inspiring stories of Jackie Robinson, who broke through Major League Baseball's color barrier in 1947; Jesse Owens, who ran roughshod over Adolf Hitler's notions of Aryan supremacy at the 1936 Berlin Olympics; and perhaps even that of Jack Johnson, the boxing great who unapologetically defied the Jim Crow norms of early 20th-century America.

However, the modern world is still catching on to the breathtaking accomplishments of Marshall "Major" Taylor, the Black bicycle racing sensation who became a world champ a decade before Johnson and captivated a still-segregated nation when the sport was reaching new heights in popularity.

Taylor got his first bike through connections to a well-off family

As told in Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer, Taylor was born in November 1878 in the rural outskirts of Indianapolis, Indiana. His father was a poor Civil War veteran; little is known about his mother.

When Taylor was about eight years old, his father was hired as a coachman for a wealthy white family named the Southards. Taylor quickly became best friends with their son, Dan, to the point where he was living with the family and enjoying access to tutoring and gifts like a brand-new bicycle.

The Southards moved to Chicago when Taylor was about 13, abruptly pulling him back to a life of poverty. He still had the bicycle, however, and after showing a bike-store owner the tricks he had learned, the teenager was hired to put on a show outside the store in a military uniform, giving rise to the nickname that would stick.

He found a mentor and moved east to launch a racing career

Taylor soon fell under the apprenticeship of bicycle racer-turned-manufacturer Louis de Franklin "Birdie" Munger, who gave the promising biker a place to stay while providing instruction on proper training and nutrition.

In June 1895, Munger helped Taylor surreptitiously enter a 75-mile race that promised a prize worth $300. In a scene that would be repeated many times in the years to come, the white riders greeted the lone Black entrant rudely and threatened him with physical harm, only to see him speed away to victory.

Taylor also notched victories at a few follow-up races, but his opportunities for competition remained limited. Sensing better business opportunities for himself and friendlier environs for his protégé, Munger convinced Taylor to move with him to Worcester, Massachusetts, later that year.

Taylor indeed enjoyed a warmer—if not entirely welcoming—reception to the East Coast racing community in 1896, as he fell in with a Black biking club and won several integrated events. He also returned to Indianapolis that summer and set unofficial records in the 1-mile and 1/5-mile races at the just-opened Capital City track, for which he was rewarded with a ban from the premises.

Taylor became just the second world champion Black athlete

Shortly after his 18th birthday, Taylor turned in an unforgettable pro debut at New York City's Madison Square Garden by beating sprinting champion Eddie "Cannon" Bald in a 1-mile race. The phenom also entered the main event, an unbelievably grueling competition in which contestants logged as many miles as possible over six days, and he managed to finish in eighth place despite suffering from exhaustion-fueled hallucinations.

With a full-blown biking craze sweeping the nation, Taylor emerged as a national figure both for his undeniable talent and his position as a Black man pushing the limits of acceptability in an athletic forum. Newspapers eagerly reported on his events—often with unflattering mentions of his race—and editorialized about the rough treatment he received, including one incident in which he was pulled from his bike by a white competitor and choked unconscious.

Taylor kept winning and drawing huge crowds to his performances, even as other riders actively tried to shut him out of the sport. Barred from entering races in the South, the "Black Cyclone" missed out on the chance to claim the national sprinting championship in 1897 and '98. Nevertheless, he closed out that latter year in spectacular fashion, setting several world records via high-profile private performances that were roundly celebrated in the press.

The pinnacle came at the 1899 World Championships in Montreal, Canada, when Taylor won the 1-mile race to become just the second Black world champion athlete, after boxer George Dixon in 1890. Hearing the "Star Spangled Banner" played to celebrate his triumph, Taylor later noted that he "felt even more American at that moment than [he] ever felt in America."

He enjoyed adoring crowds and lucrative paydays overseas

After repeatedly turning down offers of huge paydays to compete in Europe, the devoutly religious Taylor secured promises that he wouldn't have to race on the Sabbath and set sail across the Atlantic in March 1901.

The trip was a massive success, as Taylor lived up to his billing by besting the champions of Germany, Denmark, Italy and France in a series of races. While he still stood out for his skin color, Taylor earned the royal treatment everywhere he went, drawing high marks from the French press for his warmth and graciousness.

Receiving far shabbier treatment after returning stateside, Taylor happily accepted more offers to showcase his skills overseas. He spent much of the next few years between Europe and Australia, returning home for brief periods of rest and to marry his fiancée, Daisy Morris. Their only child, Rita Sydney, was named after the Australian city in which she was born.

Taylor rested his overexerted body for the next couple of years, before resurfacing in Europe in 1907. Nearing his 30s, "le Negre Volant" overcame a slow start to beat two recent French champions that summer and once again thrill an adoring press. He returned each of the next two years, but Father Time was beginning to exert a stronger pull, and Taylor called it quits after racing for the final time in 1910.

The former champ struggled in retirement and died penniless

Although he retired a rich man, it wasn't long before Taylor's fortunes turned south. He lost a sizable chunk of money in a failed investment in a new and improved automobile tire, and he struggled to find a reliable source of income.

In 1929, Taylor self-published his autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World, but by then he was already estranged from his wife and daughter and had been forced to sell his home. Worse, there wasn't much of a market for his book, as the glory days of American bike racing had already faded in the rearview mirror.

Taylor lived out his final days as he came into the world, penniless, in a Chicago YMCA. He died in June 1932 in the charity ward of the Cook County Hospital, and was buried in an unmarked grave at the Mount Glenwood Cemetery.

Fortunately, his legacy didn't just gather dust at this unassuming spot. Responding to a request to give the groundbreaking athlete a more fitting burial, bike manufacturer Frank Schwinn paid to have Taylor's remains exhumed and moved to a more prominent section of the cemetery in 1948.

In recent years, Taylor has received more notice for his achievements through bicycle clubs named in his honor and the dedication of a statue in his adopted hometown of Worcester, a fitting start toward due recognition for a man who paved the way for Johnson, Owens, Robinson and the other Black champions who followed his blazing trail.