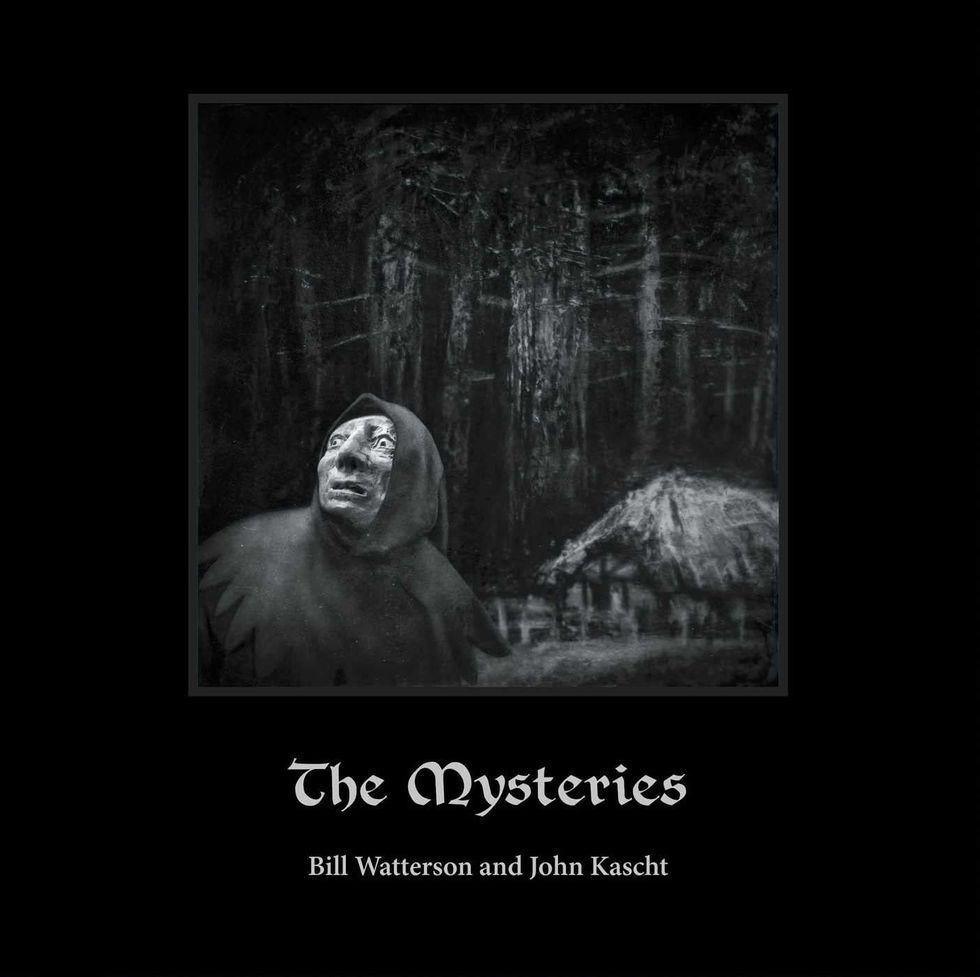

Nearly 28 years since the final strip of his wildly popular Calvin and Hobbes last graced newspaper comics, Bill Watterson is back in the headlines with his first new book since that wildly popular comic strip.

Watterson has partnered with caricaturist John Kascht on The Mysteries, which released Tuesday. Described as a “fable for grown-ups” about “what lies beyond human understanding,” it tells the story of a long-ago kingdom afflicted with “unexplainable calamities,” prompting the king to dispatch his knights to investigate.

It’s a rare new release for the famously private artist. Watterson has largely kept out of the public eye since ending Calvin and Hobbes’ 10-year run in 1995. Described by The Washington Post as “the J.D. Salinger of the strips,” Watterson gives few interviews, rarely releases new artwork publicly, and made Time’s list of most reclusive celebrities.

“He would like it all to fade away,” Watterson’s father, Jim, told the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1998. “He doesn’t get his kicks by being famous. He was just doing something he enjoyed doing.” Watterson’s mother, Kathryn, added: “He definitely wants to disappear.”

Needless to say, Watterson’s fans are overjoyed about his first major book since Calvin and Hobbes, especially because new material has been so rare for nearly three decades. Here’s what Watterson has been up to since Calvin and Hobbes ended.

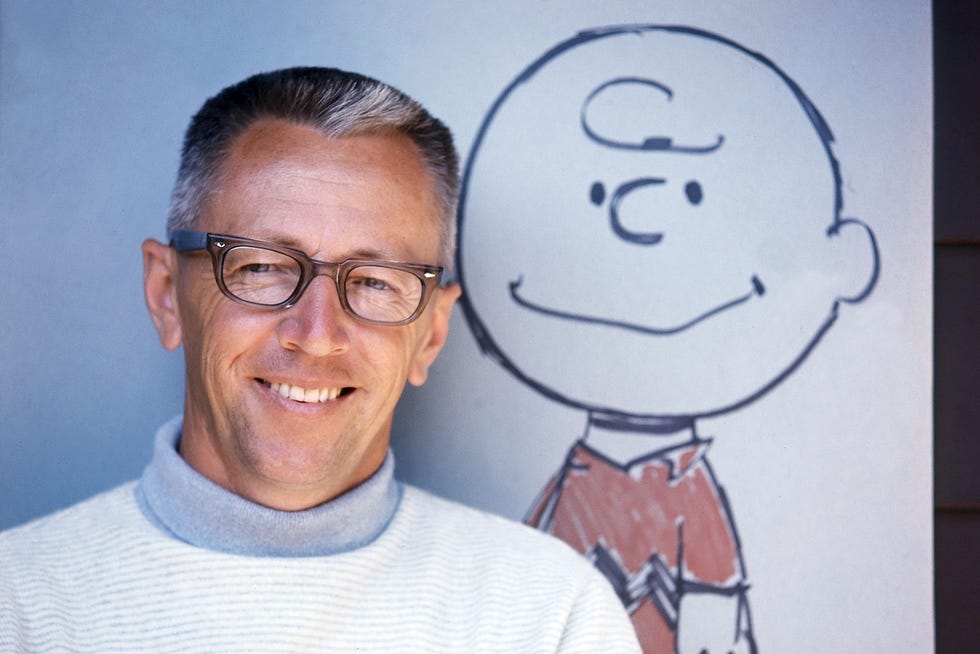

A Tribute to Peanuts’ Charles Schulz

Watterson had long described Peanuts creator Charles Schulz as one of his greatest influences. “He was a hero to me as a kid, and his influence on my work and life is long and deep,” Watterson wrote of the legendary cartoonist behind characters like Snoopy and Charlie Brown.

When Schulz died in 2000 at age 77, Watterson broke his post–Calvin and Hobbes public silence to pen a tribute to his hero for The Los Angeles Times. He described how Schulz changed the format of newspaper comics and disregarded “cinematic” visual styles in favor of simple but expressive artwork that “reveal a deep understanding of cartooning’s strengths.”

“Comic-strip cartooning requires such a peculiar combination of talents that there are very few people who are ever successful at it,” Watterson wrote. “Of those, Charles M. Schulz is in a league all his own.”

His Painting Hobby

Shortly after Calvin and Hobbes ended, Watterson took up painting, spending time creating landscapes of Ohio woods with his father. He studied a variety of artists, from the expressionist Willem de Kooning to the Italian Renaissance master Titian, according to Nevin Martell’s book Looking for Calvin and Hobbes.

But Watterson declined to publicly exhibit his work, telling Mental Floss: “I don’t paint ambitiously. It’s all catch and release: just tiny fish that aren’t really worth the trouble to clean and cook.” In fact, Martell described a rumor that Watterson was such a perfectionist that he burned his first 500 paintings because he felt they weren’t up to his standards.

Comic historian Richard West said he didn’t know if the 500 number was accurate, but “it’s not far from the truth; he’s destroyed many more paintings than he’s saved,” according to Martell’s book. Nevertheless, West called Watterson “an extraordinarily accomplished painter [who] has the fundamentals of composition, coloring, and technique down to a fine art.”

First Public Art Exhibition

Watterson unveiled one of his paintings to the public for the first time in 2011, and the subject was an unusual one: an oil portrait of Petey Otterloop, an 8-year-old character from the comic strip Cul de Sac by Richard Thompson.

When Thompson, who had Parkinson’s disease, established an art exhibit and auction in support of the Team Cul de Sac charity for Parkinson’s research, Watterson was one of more than 100 cartoonists who contributed original art for the cause.

“I was reluctant to goof around with Richard’s creation, so I had trouble thinking of an approach that interested me until I got the idea of painting a portrait,” Watterson told The Washington Post. “I thought it might be funny to paint Petey ‘seriously,’ as if this were the actual boy Richard hired as a model for his character.”

First New Cartoon Since Calvin and Hobbes

Watterson has given few interviews in his life, but he provided what he called “a few sentences” of voiceover remarks for Stripped (2014), cartoonist Dave Kellett’s documentary about comic strips. Afterward, Kellett asked Watterson if he would also draw the film’s poster.

“It sounded like fun and maybe something people wouldn’t expect, so I decided to give it a try,” Watterson told The Washington Post. “Dave sent me a rough cut of the film, and I dusted the cobwebs off my ink bottle.”

The poster features a cartoonist who literally leaps out of his clothes in surprise while reading about the demise of newspapers. Watterson said: “Given the movie’s title and the fact that there are few things funnier than human nudity, the idea popped into my head largely intact. The film is a big valentine to comics, so I tried to do something really cartoon-y.”

Watch Stripped on Prime Video

Surprise Pearl Before Swine Artist

In June 2014, three strips from the Pearl Before Swine comic featured its artist Stephan Pastis being schooled by a second-grader on how to properly draw. The child’s drawings were a different style than Pastis’ normal work, and it was later revealed that Watterson had been the one behind them.

It was Watterson’s idea to be Pastis’ secret guest cartoonist. After having read a previous Pearl Before Swine cartoon that referenced Calvin and Hobbes, Watterson said “I thought it might be funny for me to ghost Pearls sometime, just to flip it all on its head,” according to The Washington Post.

“I thought maybe Stephan and I could do this goofy collaboration and then use the result to raise some money for Parkinson’s research in honor of Richard Thompson,” Watterson added. “It just seemed like a perfect convergence.” According to the same Post article, Pastis compared being approached by the famously reclusive Watterson “like getting a call from Bigfoot.”

Colin McEvoy joined the Biography.com staff in 2023, and before that had spent 16 years as a journalist, writer, and communications professional. He is the author of two true crime books: Love Me or Else and Fatal Jealousy. He is also an avid film buff, reader, and lover of great stories.