The 15th through 17th centuries saw a wave of “witch hunts” break out across the Western world: the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts, the 1428 Valais Hexen hunts in what is now Switzerland, and the myriad persecutions in Scotland and Ireland after the passage of the Witchcraft Acts of 1563 and 1586 are only a few of the many witchcraft-related uproars that plagued Europe and America.

The idea of witches had been present in folklore all the way back to the time of the ancient Romans. But a persecution on this scale hadn’t occurred before across nations. What could have prompted these 300 years of deadly witch hunts?

A new study published in the journal Theory and Society seems to have pinpointed the source of this outbreak of witchcraft panic. And as it turns out, the culprit for the deadly craze is none other than Johannes Gutenberg.

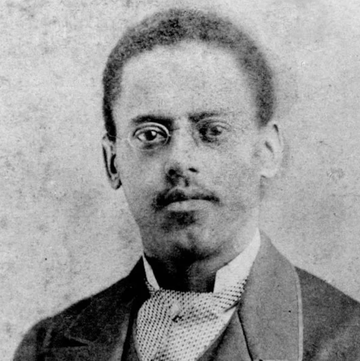

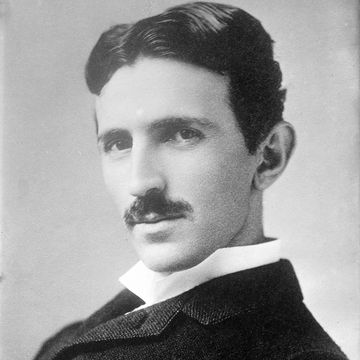

No, the famed German inventor wasn’t some master of the occult. But his most notable invention, the printing press, is what helped the massive spreading of a new theory of witchcraft in the 15th century, according to this study.

One particularly damaging mass-produced book—a text called Malleus Maleficarum, written in 1487 by Heinrich Kramer, a Dominican friar—reshaped how the Western world saw the practice of witchcraft. As the study writes, this new line of thinking “depicted witchcraft as conspiratorial activity against godly society and not simply mischief by village sorceresses, pagans, or ignorant peasants.”

More than just crafting a conspiracy theory, Malleus Maleficarum—which translates to “The Hammer of Evil-Doers”—also served as “the first printed guide for witch-hunters”:

“The book’s great innovation was to combine an elaborate theological explanation of witchcraft with practical guidance on the methods of investigating, interrogating, and convicting witches. It endorsed the use of inquisitorial methods by secular judges and argued for a relaxation of legal restraints in witchcraft prosecution. Kramer was eager to boost the apparent legitimacy of the treatise, and the first edition as well as some subsequent editions contained endorsements, including approbation by the Cologne theological faculty, a papal bull calling for suppression of witchcraft, and a German imperial decree against witches.”

From there, it spread via a route that the study deems “ideational diffusion.” More than just the adoption of certain actions by a culture, ideational diffusion represents “the adoption of new ideas, which lead social actors to reinterpret the world and thus to change their behavior.”

Thanks to the printing press, Malleus Maleficarum became an early form of mass media, easily spread amongst the elite and the literate of European society. People unable to read would inevitably hear the ideas regurgitated by the literate and spread it to their neighbors that way.

“We argue that the social logic of witch trials spread because elite actors were exposed to the ‘elaborated’ theory of witchcraft through printing and by neighbors, both of which offered a new understanding of the governance challenge confronting them and a new set of practices to address it,” the study posits, “...percolation and social interdependence fostered re-interpretation.”

The study put this theory of influence to the test, mapping out the locations and dates of various witch hunts throughout the centuries, and comparing them to where Malleus Maleficarum had been printed and distributed. “Cities closer in time and space to the publication of the Malleus were more likely to commence witch trials,” they found.

“The printing press did not cause the inception of the elaborated theory of witchcraft,” concludes the study, “...but our results show that it fostered its spread.”

Michale Natale is a News Editor for the Hearst Enthusiast Group. As a writer and researcher, he has produced written and audio-visual content for more than fifteen years, spanning historical periods from the dawn of early man to the Golden Age of Hollywood. His stories for the Enthusiast Group have involved coordinating with organizations like the National Parks Service and the Secret Service, and travelling to notable historical sites and archaeological digs, from excavations of America’ earliest colonies to the former homes of Edgar Allan Poe.