“By his deeds he shall be remembered.”

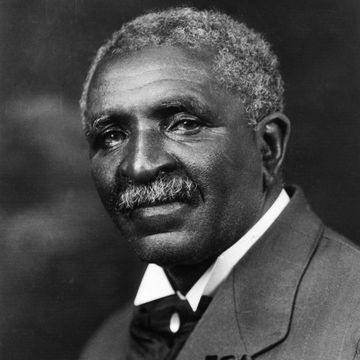

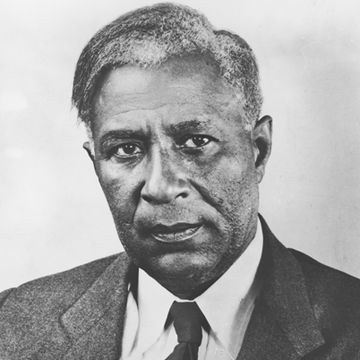

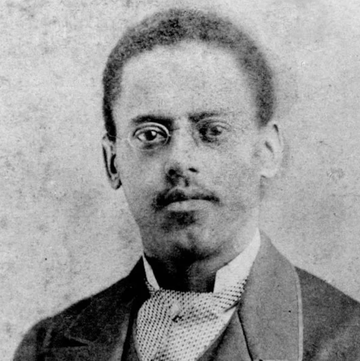

For Garrett Morgan, this epitaph on his gravestone at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland is befitting of any number of accomplishments. The Black inventor—born on March 4, 1877, to former slaves in Kentucky—had an entrepreneurial spirit that allowed him to start a successful tailoring business and create a line of hair care products. More famously, Morgan created the “safety hood,” a precursor to the World War I gas mask, as well as the prototype for the modern traffic signal, indirectly saving countless future lives with his ingenuity.

One pivotal moment showcasing Morgan’s commitment to public safety and the usefulness of his safety hood was his life-saving response to the 1916 Waterworks Tunnel disaster in Cleveland. Morgan, with the aid of his brother Frank and his now-patented device, saved two workers trapped underground in a cloud of noxious fumes and dust, plus recovered the bodies of four others.

Given that the calamity resulted in 21 deaths, not to mention impaired his own health, Morgan is now revered as a shining example of bravery and selflessness. Except more than a century ago, it seemed like this wouldn’t be the case.

Morgan shielded his identity to sell his safety hood

Morgan, who called himself the “Black Edison,” filed for a patent for his safety hood in 1912 after observing firefighters struggling with smoke inhalation. Massachusetts Institute of Technology describes the device as a canvas hood placed over the head with a series of tubes that helped filter polluted air.

The device was uniquely Morgan’s; it was the only item he both patented and manufactured, according to a 2012 article Michigan State University professor Lisa D. Cook wrote for Business History Review. Because of prevailing attitudes at the time—the 1896 verdict of Plessy v. Ferguson had made segregation legal—Morgan had to be creative to advertise and sell his product.

One way he did this was by demonstrating the product in live “road shows,” in which he would disguise himself as a Native American named Big Chief Mason. He also enlisted White actors to perform exhibitions in southern cities. His print advertising often showed White models wearing the product, according to Cook. He also listed the names of notable businessmen and civic figures prominently on his company letterhead and benefitted from word-of-mouth endorsements from magnates like John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan.

Additionally, receiving a patent for the device in 1914 proved crucial to shielding Morgan’s identity. Patent documents weren’t easily accessible in the early 1900s, and they also didn’t contain information on race. Thus, before zip codes could offer clues about an applicant’s neighborhood, Black entrepreneurs like Morgan could benefit from the prestige they offered and still remain anonymous.

Little did Morgan know the tunnel disaster two years later would spread the word about his hood more than he could have imagined.

The 1916 tunnel accident wasn’t the first

According to ClevelandWater.com, the city completed its first municipal waterworks facility in September 1856, pulling in water from Lake Erie. Prior to this, residents’ supply came from wells and surface water. But as the second Industrial Revolution took hold following the Civil War and population grew, the demand for water increased. Unfortunately, the supply was severely contaminated by sewage; rates of cholera and typhoid rapidly increased over the next four decades.

In response, the city began constructing waterworks tunnels linked farther out in the lake to an intake crib, a structure containing a shaft that collects water and supplies it to stations onshore. The first two tunnels, one finished in 1874 and the other by the mid-1890s, proved inadequate because of the rampant pollution of Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River. In 1898, construction began on a third tunnel that would lead to a new water crib 3 miles out into the lake. The project proved extremely hazardous.

According to Case Western Reserve University, a total of four gas explosions took the lives of 28 workers from 1898 through 1902. But perhaps the most horrifying incident was a fire that started in a temporary crib on August 4, 1901. Five men burned to death, three more drowned, and one died attempting to rescue victims.

Any hopes that construction on a fourth tunnel, which started in 1914, would be less dangerous were dashed when crews hit a natural gas pocket and ignited an explosion around 9:30 p.m. on July 24, 1916. This set up a mad scramble by Morgan and others to assist survivors.

Morgan was in his pajamas when he decided to help

The Carnegie Hero Fund Commission writes that the explosion was so strong, it blasted concrete blocks through the ceiling of the tunnel and mangled railroad tracks. A nine-man work crew in the tunnel at the time and two others were killed by the blast. Unaware of the complete devastation, people at the surface prepared to help.

A first rescue team of seven men helmed by Assistant Superintendent of Tunnel Construction John R. Johnston made it only 132 feet into the tunnel before five of them collapsed from the toxic fumes and a sixth turned around in retreat. Only Johnson and the retreating worker made it out alive after receiving help from lock-tender William J. Dolan.

A second team led by Gus Van Duzen, the superintendent of tunnel construction, fared no better. Additional casualties now included 10 rescuers. Four more attempts were made, with responders only able to assist two men from Van Duzen’s party to safety.

Finally, a Cleveland police officer named John Chafin who had seen Morgan’s safety hood presentation convinced authorities to ask the inventor for help in the early morning of July 25. Barefoot and in his pajama bottoms, Morgan, his brother, and a neighbor gathered as many hoods as they could and rushed to the scene.

Morgan made four trips into the tunnel, helping to save Van Duzen and another man as well as retrieve the bodies of four others. The disaster and rescue made national news, but a lot of reports failed to highlight Morgan’s efforts.

Morgan felt he wasn’t properly recognized

William M. King, a former University of Colorado professor specializing in African American studies, wrote in a 1985 article from The Journal of Negro History that news of the tunnel rescue spread across wire services. However, the Cleveland daily newspapers made little to no mention of Morgan in their reports—despite his appearance in a front-page photograph.

Morgan angrily wrote a letter to Cleveland Mayor Harry L. Davis in October 1917, asking why he wasn’t called to testify for the city’s investigation into the disaster. He bluntly accused Davis of causing him “to be deprived of the rewards which [his] work had merited in connection with the Lake Erie Tunnel Disaster.”

Morgan also surmised his race factored into why the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission didn’t present him with a prestigious Carnegie Medal, given to civilians who risk death or serious physical injury to save the lives of others, in 1917. The Hero Fund maintains this isn’t the case.

The Commission writes that of 22 people nominated for their efforts in the rescue, only four earned a Carnegie Medal, including Dolan, the lock-tender. F.M. Wilmot, the Fund manager at the time, specifically addressed Morgan’s candidacy and wrote that his contribution didn’t meet the necessary requirements. “While the act by Mr. Morgan is commendable, from the facts at hand it does not appear that it was attended by any extraordinary risk to his own life, and for this reason his case, I regret to say, has not come within the scope of the fund,” Wilmot wrote.

The reasoning was that Morgan had the aid of his safety hood, which meant he was “not at the same extraordinary risk of suffocating” by descending into the gas-filled tunnel. Still, “Morgan’s efforts, and bravery that day—he saved more people than any of the rescuers that entered the tunnel earlier—are important and should be honored,” the Fund has since concluded.

Ironically, interest in the safety hood waned from the publicity Morgan did receive. His granddaughter, Sandra Morgan, has said her family believed the public’s growing knowledge of Morgan’s identity caused sales of the product to plummet. “As far as I know, they were selling very well until it was discovered that the patent holder was Black, and then sales dried up. That was very upsetting for him,” she said.

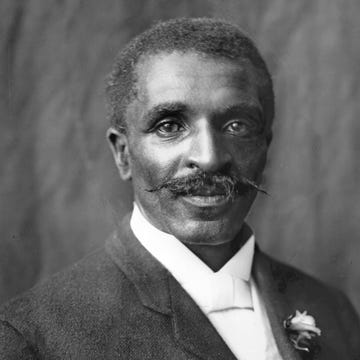

Cleveland citizens rallied around Morgan

While he might have felt spurned by the press, city officials, and a major award committee, Morgan did have the support of many of his Cleveland neighbors. On February 4, 1917, a group of citizens led by Victor W. Sincere of the Bailey Company department store decided to honor Morgan themselves. They accompanied him to the St. John’s AME Church, the first African American church established in Cleveland in 1836, and presented him with a diamond-studded gold medal.

A week later, the Cleveland Advocate posted a letter from Sincere, who offered glowing praise of Morgan’s bravery in descending “into the abyssmal depths, where death stalked.” He continued:

“It is with the hope that to your and my sons, and to all mens sons that you bravery shall be an ever lasting stimulus, and that God may vouchsafe to you and yours everlasting happiness. Your deed should serve to help break down the shafts of prejudice with which you struggle, AND is sure to be a beacon light for those that follow you in the battle for life.”

Soon after, the Cleveland Association of Colored Men, which Morgan helped create in 1908, offered him a medal of commendation. He also received a gold medal and honorary membership from the International Association of Fire Chiefs because of the safety hood’s significance.

Despite his initial frustrations over the response to his heroic act, Morgan wasn’t deterred from pursuing further innovations in public safety. In 1923, he created an improved traffic signal after happening upon an accident at a busy intersection. Later that year, he sold his patent to General Motors for $40,000—equivalent to more than $700,000 today.

Morgan also decided to start his own newspaper, the Cleveland Call, in 1920. He hoped to help Black Americans receive more fair and accurate recognition in the press.

The tunnel rescue affected Morgan’s health

According to his granddaughter, Sandra Morgan, the sale of his traffic signal patent provided Garrett financial stability for the rest of his life. However, his physical health was another matter.

King, the former professor, wrote that as quickly as two days after the tunnel explosion, a doctor named E.A. Bailey arrived at the Morgan residence to treat Garrett for nausea and vomiting. In a letter written more than a decade later, Bailey described how Morgan had “inhaled the foam and the breath of the man he was rescuing,” in this case Van Duzen.

When the superintendent was brought to the surface, doctors initially wished to use a pulmotor to help revive Van Duzen. However, Morgan stopped them because of the condition of his lungs and, as Bailey’s letter states, performed mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Given the circumstances of the accident, Morgan also likely inhaled the noxious gases present in the tunnel to some degree.

In 1927, Morgan requested compensation from the city, claiming he had suffered more from the incident than he originally believed. A 1929 letter makes reference to an emergency ordinance for the Cleveland City Council, which proposed compensating Morgan the amount of $2,000 for “supposed injuries sustained in relief work in the water works tunnel disaster.” However, the council director performed an inquiry into the matter and concluded the claim shouldn’t be approved. The city manager similarly determined the claim had no legal basis, though he felt the city had a moral obligation to pay Morgan.

By 1943, Morgan had developed glaucoma and lost most of his eyesight. He blamed health troubles he had in his later years on what happened during the rescue and eventually died on July 27, 1963, at age 86 after battling an unspecified “lingering illness.”

Morgan’s accomplishments are now well-known

More than 100 years after the creation of both his safety hood and traffic signal, Morgan’s impact as an inventor is well-documented. Even prior to his death, the U.S. government honored him for his work on the traffic signal. Then, in 2005, he was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Akron, Ohio, not far from his former home in Cleveland.

Similarly, the U.S. Federal Highway Administration has named an educational opportunity in his honor. The Garrett A. Morgan Transportation Technology Education Program encourages students in STEM to pursue careers in the transportation industry.

As for Morgan’s rescue efforts in 1916, the Cleveland Water Department has ensured his selfless deed won’t go unnoticed anymore. In 1991, its Division Avenue Station became the Garrett A. Morgan Water Treatment Plant in recognition of his actions in the crisis and contributions to science and industry.

Twenty-five years later, and marking the 100th anniversary of the tunnel incident, the facility now bearing Morgan’s name hosted a ceremony in July 2016 to honor the inventor, other rescuers, and the victims involved in the Waterworks disaster. Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson was in attendance as well as Sandra Morgan, who held back tears as she addressed the crowd, including multiple descendants of those involved in the tragedy.

“It was amazing to be a part of that because we all have our sides of that story,” she later said. “It was really very touching and the first time; it took a hundred years to pull us all together, which I think was pretty amazing.”

Much like the support he received from members of the Cleveland community a century prior, their memories of that fateful day help ensure Morgan’s life-saving actions aren’t lost to history.

Tyler Piccotti joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor and is now the News and Culture Editor. He previously worked as a reporter and copy editor for a daily newspaper recognized by the Associated Press Sports Editors. In his current role, he shares the true stories behind your favorite movies and TV shows and profiles rising musicians, actors, and athletes. When he's not working, you can find him at the nearest amusement park or movie theater and cheering on his favorite teams.