Even compared to today's modern athletes, with their access to advanced training and nutritional knowledge, Lou Gehrig was a physical specimen.

His immense power and durability enabled him to compile some of the most impressive statistics in Major League Baseball history as a first baseman for the New York Yankees. It also allowed him to achieve one of the most famous records across all sports—an incredible 2,130 consecutive games played from 1925 to 1939 (a mark since surpassed by Cal Ripken Jr.).

Yet, while the "Iron Horse" is known as one of baseball's all-time greats, he is also remembered for the disease that robbed him of his celebrated strength and vitality and suddenly cut him down in the prime of his life—Lou Gehrig's disease.

Lou Gehrig's symptoms first surfaced in his mid 30s

As described in Jonathan Eig's Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig, the first signs of trouble surfaced ahead of the 1938 season. Having spent a chunk of his offseason filming the Western Rawhide (1938) in Hollywood, the normally fit Gehrig was admittedly out of shape when he arrived at the Yankees' training camp in March.

Gehrig feverishly worked to get up to speed, but his hands ached and he wasn't whacking the ball with his usual thump. When his poor performance continued through the first weeks of the season, Yankees manager Joe McCarthy dropped the struggling slugger from his customary fourth spot in the batting order to fifth and then sixth.

Gehrig began hitting well enough to quiet concerns that playing every day wore him down, but something still wasn't right. McCarthy asked him why he wasn't swinging with his usual power, and others noted that he seemed slow and awkward while running the bases. Meanwhile, Gehrig was tinkering with his batting stance and using lighter bats to find a comfort level that never fully materialized.

He finished the season with a .295 batting average and 29 home runs, numbers that failed to match his usual lofty standards, but were robust enough to suggest that, at 35, he still had a few good years left as a ballplayer.

That winter, however, as Gehrig began stumbling over curbs and inexplicably dropping things, it was clear that his problems had progressed past an inability to catch up with a good fastball. His wife, Eleanor, worried that her husband had a brain tumor; a doctor instead diagnosed the slugger with a bad gallbladder and placed him on a strict diet of fruits and vegetables.

Gehrig benched himself early in the 1939 season

When training camp began in March 1939, Gehrig's physical deterioration and rapidly eroding skills had become painfully obvious to fellow players and sportswriters covering the team.

At one point, a young Joe DiMaggio was startled to watch Gehrig swing at and miss 19 consecutive batting-practice pitches. Another teammate was shaken when Gehrig suddenly fell over backward in the middle of their locker-room discussion.

A loyal McCarthy kept Gehrig in the lineup to begin the season, even as the once formidable star struggled to collect hits and field his position. Yet, it was a play he did make, on an easy grounder to first that had teammates lining up to congratulate him, that made him realize what a liability he had become.

On the morning of May 2, Gehrig informed his manager that it was best if he came out of the lineup. His consecutive-games streak finished after 14 years, he acknowledged the warm ovation from the Detroit fans before that day’s game, before taking a long drink from the dugout fountain to hide his tears from teammates.

He received a diagnosis after visiting the Mayo Clinic

Gehrig continued to suit up and travel with the team, even though he was absent from the lineup through May and into June. He did attempt a comeback during a game against a minor league team on June 12, only to abandon the effort after getting knocked over by a line drive.

The following day, Gehrig checked into the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, hoping to finally receive some information about his condition. It didn't take long for the answer to come to his first attending physician, who recognized in the "telltale twitchings" of Gehrig’s muscles the same ailment that had killed his own mother.

Following a week in Minnesota, Gehrig returned with a letter that revealed a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a neurological disease that progressively robs its patients of the ability to control voluntary movements. The report failed to mention the grim prognosis that awaited Gehrig–most patients die after three to five years from respiratory failure–though it did note that he could no longer continue as a player. The news was relayed to the public on June 21, with the announcement that Gehrig was retiring from baseball.

July 4 was marked as Lou Gehrig Day at Yankee Stadium, with a ceremony held between games of a doubleheader against the Washington Senators. Never comfortable in the spotlight, the man of honor initially backed away from addressing the crowd before hobbling to the microphone to deliver his famous words:

"For the past two weeks, you've been reading about a bad break," he said, his voice cracking. "Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth."

Gehrig signed on for experimental treatments

Whether or not he truly felt lucky, Gehrig was optimistic about his chances of surviving this little-known disease. He returned to the Mayo Clinic in late August and received an encouraging report. "I've been feeling right along with that I was getting better,” he said in an interview at the time. "But it is good to get the news direct from headquarters."

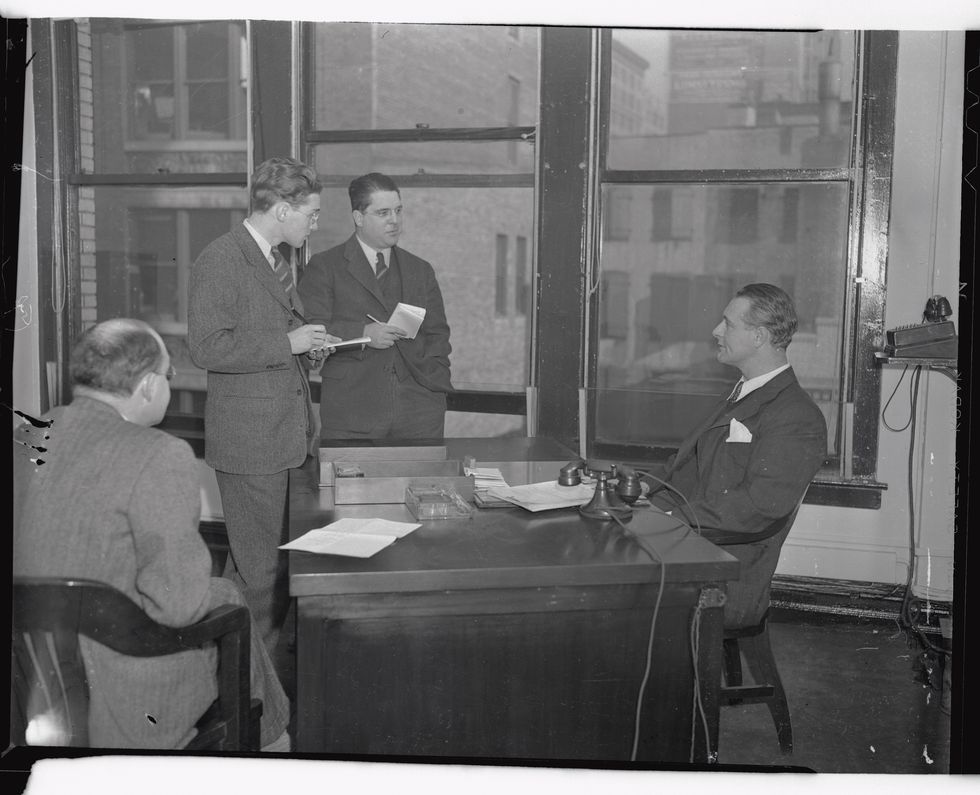

In October, New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia announced he appointed Gehrig to a 10-year post as commissioner of the city's parole board. It was a role that suited the ex-ballplayer well, as he enjoyed the opportunity to influence the incarcerated young men and women he encountered and otherwise conserved his precious energy while processing stacks of paperwork in his office.

Gehrig began undergoing more experimental treatments by early 1940. One doctor at the Mayo Clinic espoused the wonders of histamine, while another in New York was convinced of the healing powers of vitamin E. Gehrig also occasionally tried out the supplements and therapeutic oils sent by well-meaning physicians. Nothing made a real difference in the attempt to stem the loss of strength in his limbs.

That summer, insult was added to injury when a Daily News writer suggested that the Yankees' poor play was the result of Gehrig transmitting his sickness to his former teammates. An incensed Gehrig sued the newspaper, eventually settling out of court with a signed agreement.

He attempted to continue his job as he struggled with daily tasks

By early 1941, Gehrig struggled to ingest soft foods without choking and could no longer walk without assistance. He still made the daily trip downtown for his job, with Eleanor essentially handling all responsibilities, until he requested a six-month leave of absence in mid-April.

His mind unaffected by the disease that was destroying his body, Gehrig suffered through bouts of depression, though he usually pulled himself together for visitors. In May, old teammate Tommy Henrich and a few writers made the trip to Gehrig's home in the Bronx, where they talked baseball with the bedridden ex-ballplayer. Now down to around 125 pounds, in Henrich's estimate, Gehrig told his guests that he'd likely hit rock bottom before he recovered.

A few weeks later, on the morning of June 2, the Iron Horse lapsed into a coma. He was declared dead that evening, less than three weeks shy of his 38th birthday, from the disease that would bear his name as it slowly revealed its true nature to medical researchers in the following decades.