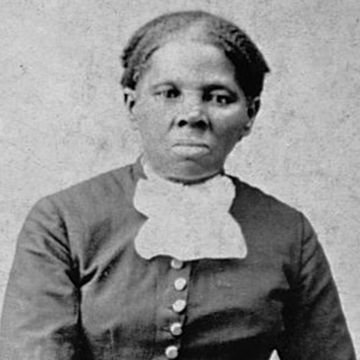

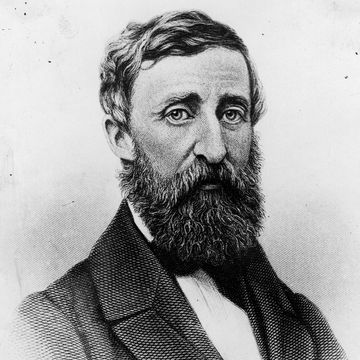

c. 1795-1858

Who Was Dred Scott?

Dred Scott was born into slavery sometime around 1795 and made history decades later by launching a legal battle to gain his freedom. Scott and his family had spent time in two free states while working for their owner John Emerson. After Emerson died, Scott tried and failed to buy freedom for himself and his family. He took his case to the Missouri courts, where he won, only to have the decision overturned. Scott’s federal case wound up at the U.S. Supreme Court. The court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford was handed down on March 6, 1857, and also denied Scott’s freedom. The extremely controversial event was a precursor for Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil War. Scott died in his 60s in 1858, prior to either event.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Dred Scott

BORN: circa 1795

DIED: September 17, 1858

BIRTHPLACE: Southampton County, Virginia

SPOUSE: Harriet Robinson (1836-1858)

CHILDREN: Eliza, Lizzie, and two sons who died in infancy

Born Into Slavery

Dred Scott was born into slavery sometime around the turn of the 19th century, often fixed at 1795, in Southampton County, Virginia. Legend has it that his name was Sam, but when his elder brother died, he adopted his name instead.

His parents were enslaved, possibly by the Blow family at the time of Scott’s birth, though they might have been purchased after. Peter Blow and his family relocated first to Huntsville, Alabama, and then to St. Louis. After Peter died in the early 1830s, Scott was sold to a U.S. Army doctor named John Emerson.

In 1836, 40-year-old Scott fell in love with 19-year-old Harriett Robinson, who was enslaved by another army doctor. In a move that was unusual in an era when marriages between enslaved people were often not considered valid, and families could be easily separated at will, Harriet and Dred were married in a civil service. Her ownership was transferred over to Emerson when they were wed. The couple had four children. Daughter Eliza was born in 1838, followed by another daughter, Lizzie, born in 1844, and two sons who died shortly after their birth.

In the ensuing years, Emerson traveled to Illinois and the Wisconsin Territories, both of which prohibited slavery. When the doctor died in 1846, Scott tried to buy freedom for himself and his family from Emerson’s widow, Irene Emerson, for $300 but she refused.

Dred Scott v. Sandford Case and Decision

Scott made history by launching a legal battle to gain his freedom. That he had lived with his late owner John Emerson in free territories became the basis for his case.

The process began in 1846 when Dred and his wife, Harriet, filed separate lawsuits against John’s widow, Irene Emerson. Neither could read or write, so they obtained legal, financial, and logistical assistance from friends and abolitionist supporters. The Scotts lost in this initial suit in a local St. Louis district court but won in a second trial, only to have that decision overturned by the Missouri State Supreme Court.

With support from local abolitionists, Dred filed another suit in federal court in 1854 against John Sanford, Irene’s brother and executor of John Emerson’s estate. When that case was decided in favor of Sanford, Scott turned to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford was issued 11 years after the initial suits. Seven of the nine judges agreed with the outcome delivered by Chief Justice Roger Taney, who announced that enslaved people were not citizens of the United States and, therefore, had no rights to sue in Federal courts: “They had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

The decision also declared that the Missouri Compromise, which had allowed Scott to sample freedom in Illinois and Wisconsin, was unconstitutional and that Congress didn’t have the authority to prohibit slavery. Eventually, the 13th and 14th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution overrode this ruling.

Life After the Court Decision

The Dred Scott decision sparked outrage in the northern states and glee in the South. The growing schism made the Civil War inevitable.

Too controversial to retain the Scotts after the trial, Irene Emerson remarried and returned Dred and his family to the Blows, who granted them their freedom in May 1857. Scott and his family stayed in St. Louis after emancipation, and he found work as a porter in a local hotel.

Death

After a little more than a year of true freedom, Scott died from tuberculosis on September 17, 1858, in St. Louis.

Scott is buried in that city’s Calvary Cemetery. Putting pennies (displaying the face of President Abraham Lincoln) on Scott’s headstone has become a local tradition over the decades. The commemorative marker next to the headstone reads: “In Memory Of A Simple Man Who Wanted To Be Free.”

Harriet survived her husband by 18 years and is buried in Hillsdale, Missouri. In 1997, both she and Dred were admitted to the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

Historical Importance of the Dred Scott Decision

Dred Scott’s fight for his freedom reverberated throughout the nation and remains a critical part of American history.

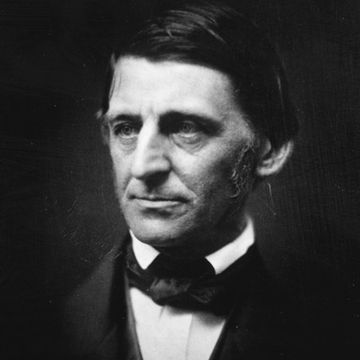

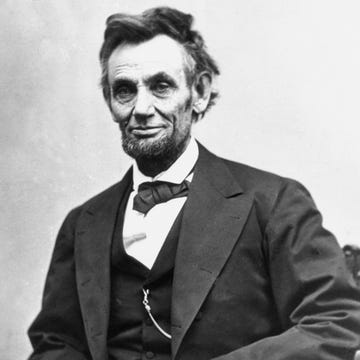

In December 1856, months before the decision was announced, a former one-term U.S. Congressman from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, delivered a speech harshly criticizing the Dred Scott Case and examining its constitutional implications. Lincoln, who at this time favored halting the spread of slavery in the United States but not its immediate abolition, used the debate over slavery to propel himself to the Republican presidential nomination and then the presidency in 1860.

By that time, the Supreme Court’s controversial Dred Scott decision (1857) had worsened tensions in a nation already divided over the issue of slavery. Many Southerners welcomed the decision, believing the government had no role to play in the issue. In contrast, many in the North attacked the judgment, believing it would inevitably lead to the spread of slavery throughout more of the country. The same month that the Scott family was freed, Frederick Douglass delivered a speech discussing the Dred Scott decision on the anniversary of the American Abolition Society, using it as a rallying cry for the anti-slavery cause.

Despite President Lincoln’s then-more moderate positions on the issue, several states seceded within months of his inauguration in 1861, and the American Civil War began. For the first two years of the war, Lincoln’s goals remained to end the war and reunite the Union. However, as the conflict deepened, his views began to shift, influenced, in part, by the advocacy of Douglass and other abolitionists, who saw the war as a chance to strike a final blow in slavery by freeing the nearly 4 million enslaved Americans.

Lincoln began to act. Knowing that depriving Confederate states of the enslaved labor would also weaken their ability to wage war, he allowed Union armies to confiscate captured Confederate “property,” including enslaved people in Southern states, leading to a flood of enslaved people rushing to Union lines to secure their freedom.

Then, in late 1862, he announced a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, to take effect on January 1, 1863, to free all enslaved people in states still in rebellion against the Union. He later fulfilled another aim of Douglass and other Black leaders by allowing Black soldiers, including the formerly enslaved, to serve in the Union Army. Lincoln also championed passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery nationwide, which was finally ratified in December 1865, months after his assassination.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us