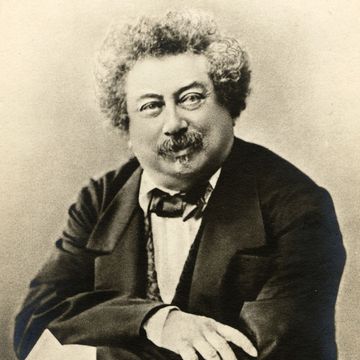

1818-1895

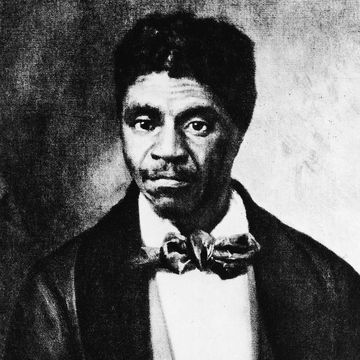

Who Was Frederick Douglass?

Abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass was born into slavery sometime around 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland. He became one of the most famous intellectuals of his time, advising presidents and lecturing to thousands on a range of causes, including women’s rights and Irish home rule. Among Douglass’ writings are several autobiographies eloquently describing his experiences in slavery and his life after the Civil War, including the well-known work Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey

BORN: c. 1818

BIRTHPLACE: Talbot County, Maryland

DIED: February 20, 1895

SPOUSES: Anna Murray (c. 1838-1882) and Helen Pitts (1884-1895)

CHILDREN: Rosetta, Lewis, Frederick Jr., Charles, and Annie

Early Life

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born around 1818 into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland. As was often the case with slaves, the exact year and date of Douglass’ birth are unknown, though later in life he chose to celebrate it on February 14.

Douglass initially lived with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. At a young age, Douglass was selected to live in the home of the plantation owners, one of whom may have been his father.

His mother, who was an intermittent presence in his life, died when he was around 10.

Education

Defying a ban on teaching slaves to read and write, Baltimore slaveholder Hugh Auld’s wife Sophia taught Douglass the alphabet when he was around 12. When Auld forbade his wife to offer more lessons, Douglass continued to learn from white children and others in the neighborhood.

It was through reading that Douglass’ ideological opposition to slavery began to take shape. He read newspapers avidly and sought out political writing and literature as much as possible. In later years, Douglass credited The Columbian Orator with clarifying and defining his views on human rights.

Douglass shared his newfound knowledge with other enslaved people. Hired out to William Freeland, he taught other slaves on the plantation to read the New Testament at a weekly church service.

Interest was so great that in any week, more than 40 slaves would attend lessons. Although Freeland did not interfere with the lessons, other local slave owners were less understanding. Armed with clubs and stones, they dispersed the congregation permanently.

With Douglass moving between the Aulds, he was later made to work for Edward Covey, who had a reputation as a “slave-breaker.” Covey’s constant abuse nearly broke the 16-year-old Douglass psychologically. Eventually, however, Douglass fought back, in a scene rendered powerfully in his first autobiography. After losing a physical confrontation with Douglass, Covey never beat him again.

How did Frederick Douglass escape slavery?

Douglass tried to escape from slavery twice before he finally succeeded.

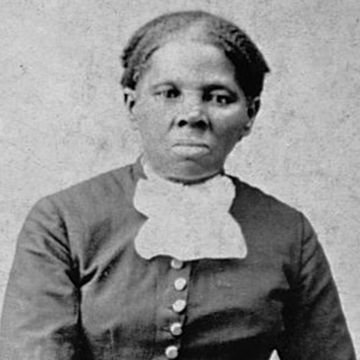

On September 3, 1838, Douglass boarded a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. Anna Murray, a free Black woman, provided him with some of her savings and a sailor’s uniform. He carried identification papers obtained from a free Black seaman. Douglass made his way to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York in less than 24 hours.

Once he had arrived, Douglass sent for Murray to meet him in New York, where they married on September 15, 1838, and adopted the name of Johnson to disguise Douglass’ identity. Anna and Frederick then settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, which had a thriving free Black community. There they adopted Douglass as their married name.

Abolitionist

After settling as a free man with his wife Anna in New Bedford in 1838, Douglass was eventually asked to tell his story at abolitionist meetings, and he became a regular anti-slavery lecturer.

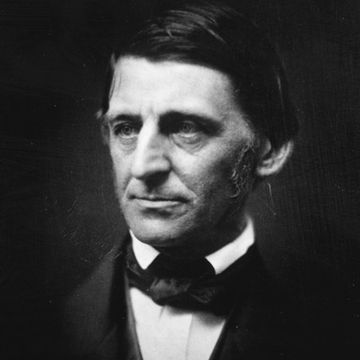

The founder of the weekly journal The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison, was impressed with Douglass’ strength and rhetorical skill and wrote of him in his newspaper. Several days after the story ran, Douglass delivered his first speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s annual convention in Nantucket.

Crowds were not always hospitable to Douglass. While participating in an 1843 lecture tour through the Midwest, Douglass was chased and beaten by an angry mob before being rescued by a local Quaker family.

Following the publication of his first autobiography in 1845, Douglass traveled overseas to evade recapture. He set sail for Liverpool on August 16, 1845, and eventually arrived in Ireland as the Potato Famine was beginning. He remained in Ireland and Britain for two years, speaking to large crowds on the evils of slavery.

During this time, Douglass’ British supporters gathered funds to purchase his legal freedom. In 1847, the famed writer and orator returned to the United States a free man.

Upon his return, Douglass produced some abolitionist newspapers: The North Star, Frederick Douglass Weekly, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Douglass’ Monthly and New National Era.

The motto of The North Star was “Right is of no Sex–Truth is of no Color–God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.”

Books: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass and More

In New Bedford, Massachusetts, Douglass joined a Black church and regularly attended abolitionist meetings. He also subscribed to Garrison’s The Liberator.

At the urging of Garrison, Douglass wrote and published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, in 1845. The book was a bestseller in the United States and was translated into several European languages.

Although the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass garnered Douglass many fans, some critics expressed doubt that a former enslaved person with no formal education could have produced such elegant prose.

Douglass published three versions of his autobiography during his lifetime, revising and expanding on his work each time. My Bondage and My Freedom appeared in 1855.

In 1881, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892.

Women’s Rights

In addition to abolition, Douglass became an outspoken supporter of women’s rights. In 1848, he was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls convention on women’s rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked the assembly to pass a resolution stating the goal of women’s suffrage. Many attendees opposed the idea.

Douglass, however, stood and spoke eloquently in favor, arguing that he could not accept the right to vote as a Black man if women could not also claim that right. The resolution passed.

Yet Douglass would later come into conflict with women’s rights activists for supporting the Fifteenth Amendment, which banned suffrage discrimination based on race while upholding sex-based restrictions.

Civil War and Reconstruction

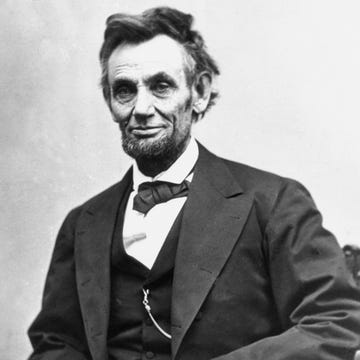

By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous Black men in the country. He used his status to influence the role of African Americans in the war and their status in the country. In 1863, Douglass conferred with President Abraham Lincoln regarding the treatment of Black soldiers, and later with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of Black suffrage.

President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of enslaved people in Confederate territory. Despite this victory, Douglass supported John C. Frémont over Lincoln in the 1864 election, citing his disappointment that Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for Black freedmen.

Slavery everywhere in the United States was subsequently outlawed by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Political Career and Vice Presidential Candidacy

Douglass was appointed to several political positions following the war. He served as president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank and as chargé d'affaires for the Dominican Republic.

After two years, he resigned from his ambassadorship over objections to the particulars of U.S. government policy. He was later appointed minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti, a post he held between 1889 and 1891.

In 1877, Douglass visited one of his former owners, Thomas Auld. Douglass had met with Auld’s daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, years before. The visit held personal significance for Douglass, although some criticized him for the reconciliation.

Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States as Victoria Woodhull’s running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket in 1872.

Nominated without his knowledge or consent, Douglass never campaigned. Nonetheless, his nomination marked the first time that an African American appeared on a presidential ballot.

Wife and Children

After their 1838 marriage, Douglass and Anna had five children together: Rosetta, Lewis Henry, Frederick Jr., Charles, and Annie, who died at the age of 10. Charles and Rosetta assisted their father in the production of his newspaper The North Star.

Anna remained a loyal supporter of Douglass’ public work, despite marital strife caused by his relationships with several other women. According to the National Park Service, she worked binding shoes and doing laundry to keep the family out of debt. Although she was a free woman, she did not read or write, so little is known about her personal life.

Anna died on August 4, 1882, at their Cedar Hill home near Washington, D.C. She was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, N.Y.

Marriage to Helen Pitts

After Anna’s death, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a feminist from Honeoye, New York. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts Jr., an abolitionist colleague. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, Pitts worked on a radical feminist publication and shared many of Douglass’ moral principles.

Their marriage caused considerable controversy, since Pitts was white and nearly 20 years younger than Douglass. Douglass’ children were especially displeased with the relationship. Nonetheless, Douglass and Pitts remained married until his death 11 years later.

Death

Douglass died on February 20, 1895, of a massive heart attack or stroke shortly after returning from a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. A church service was held at Metropolitan Methodist Episcopal Church, where Susan B. Anthony shared remarks from Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Douglas was also buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester.

Upon his passing, Douglass bestowed his Cedar Hill home and 15 acres to his widow, Helen Pitts Douglass. Members of Douglass’ family challenged the will, prompting Pitts to take out a mortgage of $15,000 to out out their respective claims.

Statues and Monuments

In June 1900, Congress chartered the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association (FDMHA) in an effort to preserve Douglass’ Cedar Hill home and its contents. Pitts left the residence to the organization upon her death in 1903. Today, the property is administered by the National Park Service as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

Douglass, became the namesake for a number of public facilities, including high schools across the U.S. and the airport serving Rochester—known as the Frederick Douglass Greater Rochester International Airport.

Multiple statues and monuments honoring Douglass exist, including in New York City’s Central Park, at Emancipation Hall of the U.S. Capitol Visitor’s Center, and several throughout Rochester.

Quotes

- If there is no struggle there is no progress. . . . Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.

- Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have the exact measure of the injustice and wrong which will be imposed on them.

- I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others, rather than to be false, and to incur my own abhorrence.

- No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.

- People might not get all they work for in this world, but they must certainly work for all they get.

- I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.

- Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.

- The life of the nation is secure only while the nation is honest, truthful, and virtuous.

- [I]n all the relations of life and death, we are met by the color line. We cannot ignore it if we would, and ought not if we could.

- If I ever had any patriotism, or any capacity for the feeling, it was whipt out of me long since by the lash of the American soul-drivers.

- The ground which a colored man occupies in this country is, every inch of it, sternly disputed.

- The lesson of all the ages on this point is, that a wrong done to one man is a wrong done to all men. It may not be felt at the moment, and the evil day may be long delayed, but so sure as there is a moral government of the universe, so sure will the harvest of evil come.

- Believing, as I do firmly believe, that human nature, as a whole, contains more good than evil, I am willing to trust the whole, rather than a part, in the conduct of human affairs.

- To educate a man is to unfit him to be a slave.

- To deny education to any people is one of the greatest crimes against human nature. It is easy to deny them the means of freedom and the rightful pursuit of happiness and to defeat the very end of their being.

- There is no negro problem. The problem is whether the American people have loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough, to live up to their own constitution.

- Let us have no country but a free country, liberty for all and chains for none. Let us have one law, one gospel, equal rights for all, and I am sure God’s blessing will be upon us and we shall be a prosperous and glorious nation.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor and is now the News and Culture Editor. He previously worked as a reporter and copy editor for a daily newspaper recognized by the Associated Press Sports Editors. In his current role, he shares the true stories behind your favorite movies and TV shows and profiles rising musicians, actors, and athletes. When he's not working, you can find him at the nearest amusement park or movie theater and cheering on his favorite teams.