1931–2019

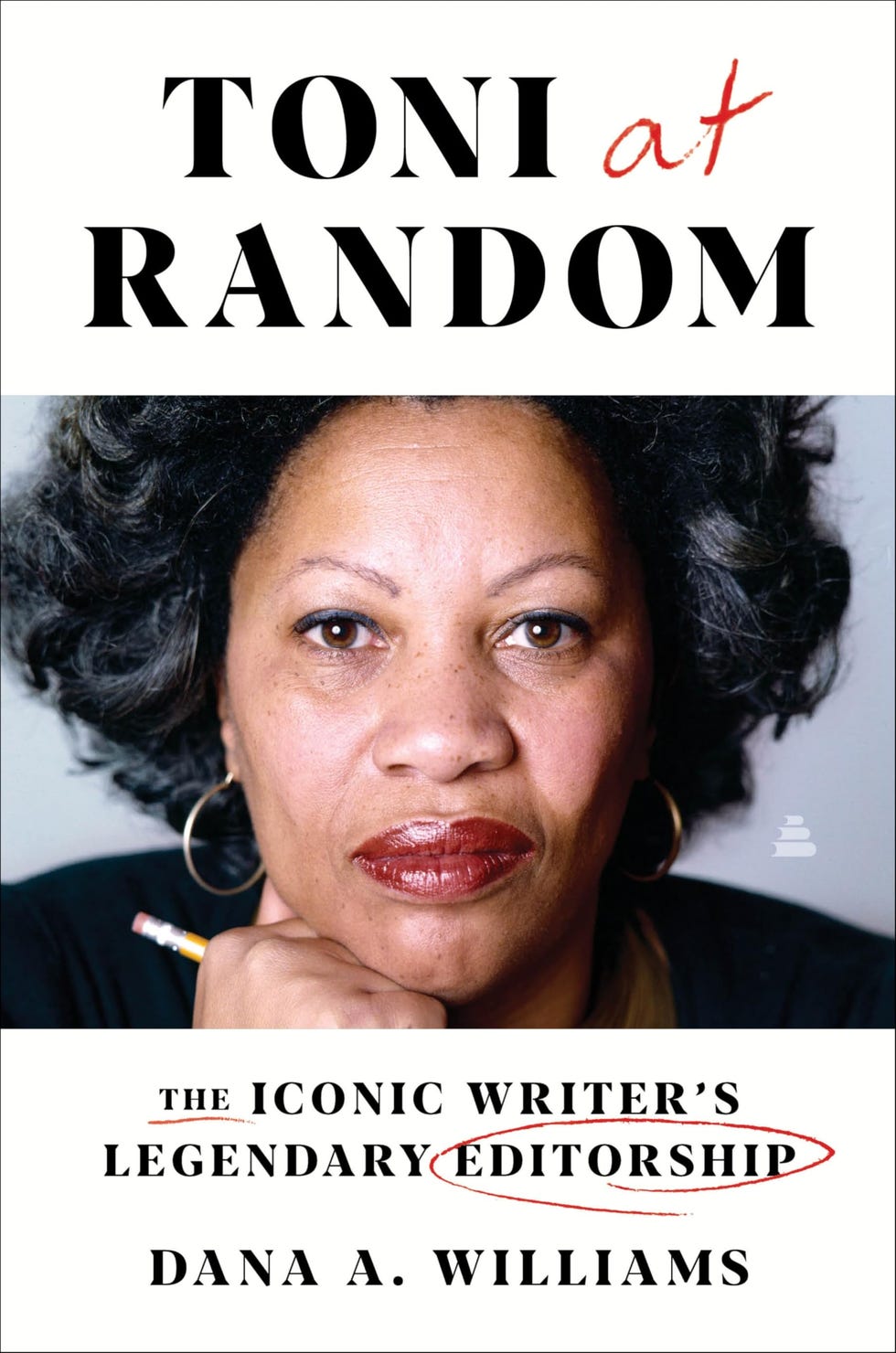

Who Was Toni Morrison?

Toni Morrison was a Nobel Prize– and Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist, editor, and professor. Her novels are known for their epic themes, exquisite language, and richly detailed Black characters. The most famous and well-regarded are Beloved, The Bluest Eye, Sula, and Song of Solomon. In 1993, Morrison became the first Black woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. Despite her worldwide acclaim, the Ohio native was rarely writing full-time. She balanced working on her books with editing for Random House as well as teaching at Princeton and Howard Universities. Through her own novels and the books she edited, she was instrumental in developing the canon of Black American literature. Morrison died in 2019 at age 88.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Chloe Anthony Morrison

BORN: February 18, 1931

DIED: August 5, 2019

BIRTHPLACE: Lorain, Ohio

SPOUSE: Harold Morrison (1958–1964)

CHILDREN: Ford and Slade

ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Aquarius

Early Life

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford on February 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio, a small city about 30 miles west of Cleveland. She was the second oldest of four children. Her father, George Wofford, worked primarily as a welder but held several jobs at once to support the family. Her mother, Ramah, was a domestic worker.

Chloe credited her parents with instilling in her a love of reading, music, and folklore as they also helped her develop a strong sense of clarity and perspective. At age 12, the girl converted to Catholicism and chose Anthony as her baptismal name after Saint Anthony of Padua.

The Wofford family lived in an integrated neighborhood, and Chloe didn’t become fully aware of racial divisions until she was in her teens. “When I was in first grade, nobody thought I was inferior. I was the only Black in the class and the only child who could read,” she once told a New York Times reporter.

Dedicated to learning, Chloe studied Latin and read many of the great works of European literature. She was also on the staff of Lorain High School’s student newspaper. She graduated with honors in 1949.

At Howard University, Chloe majored in English and minored in Classics. It was during her college years that she adopted the nickname Toni. Throughout her life, people had mispronounced her uncommon first name. When someone mistakenly called her Toni, she answered, and the name stuck.

After earning her bachelor’s degree from Howard in 1953, Toni went to graduate school at Cornell University and continued studying English. Her thesis focused on the works of Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner. She completed her master’s degree in 1955.

Teaching and Editing

Morrison’s first job was teaching at Texas Southern University. Two years later, in 1957, she returned to Howard University to teach English as a faculty member. She also joined a campus writers group and began working a short story, which later became her first novel.

Morrison decided to leave Howard in 1963. After spending the summer traveling with her family in Europe, she returned to Ohio as her marriage broke down.

In 1965, she relocated to Syracuse, New York, to work as a textbook editor for L.W. Singer, which was owned by Random House. Morrison spent her free time developing her short story from Howard’s writers group into a novel. Within a few years, she was living in New York City and editing trade books for Random House. Among notable titles she worked on were The Black Book, a 1974 anthology about Black life and history in the United States, as well as Contemporary African Fiction, a 1972 collection of African authors that included Chinua Achebe and Bessie Head.

Eventually, Morrison became Random House’s first Black female editor of fiction. She edited works by Toni Cade Bambara and Gayl Jones, renowned for their literary fiction, as well as public figures such as activist Angela Davis and boxer Muhammad Ali.

“I look very hard for black fiction because I want to participate in developing a canon of Black work,” Morrison once said. “We’ve had the first rush of Black entertainment, where Blacks were writing for whites, and whites were encouraging this kind of self-flagellation. Now we can get down to the craft of writing, where Black people are talking to Black people.”

Morrison had been contributing to that canon as an editor and simultaneously as a published author for many years. The rising literary star was appointed to the National Council on the Arts in 1980. Three years later, she left Random House to focus on her writing full-time.

Six years later, Morrison returned to academia as the Robert F. Goheen Professor at Princeton University. She taught literature, creative writing, and African American studies. Morrison was the founding director of the Princeton Atelier, which partners students with well-known artists to workshop projects. She retired from the university in 2006.

Books

Morrison didn’t publish her first book until she was 39, but from then on, she was a literary star; a writer whose acclaimed work was taught in high schools and seen in movies and on Broadway. Her name became synonymous with bringing Black culture and literature into the previously exclusive world of white publishing. Ironically, though, Morrison once told NPR’s Fresh Air that she had hoped to publish under her maiden name. “I really would have preferred Toni Wofford,” she said, but the publisher of her first book had already registered it under “Toni Morrison.”

The prolific author wrote 11 novels, two novellas, books for children, and several nonfiction books, some of which collected her articles and essays. She also penned multiple plays and opera librettos.

Many of her novels are historical, given her background as a classics scholar, but they combine highly literary aspects with accessible plots and characters. As for overarching themes, most of Morrison’s work explores slavery at various times in history, contends with how gender influences the lived experiences of men and women, and celebrates Black American culture, especially in music and geography. Because her novels take place in different times and places, over her lifetime as a writer, Morrison revealed the effects of generational trauma particularly in regard to racism and sexism in families and the larger community.

Her novels, in order of release, are:

Beginning in 1999, Morrison branched out to children’s literature. She worked with her son Slade, an artist, on The Big Box (1999), The Book of Mean People (2002), The Ant or the Grasshopper? (2003), and Little Cloud and Lady Wind (2010).

Nonfiction Books

In addition to her many novels, Morrison wrote nonfiction, as well. Her first work was Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992). She published a collection of essays, reviews, and speeches called What Moves at the Margin in 2008.

A champion of the arts, Morrison spoke out about censorship in October 2009 after a Michigan high school banned one of her books. She also served as editor for Burn This Book, a collection of essays on censorship and the power of the written word, published the same year. Morrison told a crowd gathered for the launch of the Free Speech Leadership Council about the importance of fighting censorship. She said, in part:

“The thought that leads me to contemplate with dread the erasure of other voices, of unwritten novels, poems whispered or swallowed for fear of being overheard by the wrong people, outlawed languages flourishing underground, essayists’ questions challenging authority never being posed, unstaged plays, canceled films—that thought is a nightmare. As though a whole universe is being described in invisible ink.”

In 2017, the author released The Origin of Others—an exploration on race, fear, mass migration, and borders—based on her Norton lectures at Harvard University. Two years later, her final book arrived. Similar to What Moves at the Margin, 2019’s The Source of Self-Regard compiled essays and speeches from her four decades as an author.

Awards: Pulitzer Prize, Nobel Prize, and More

Morrison’s novels drew a slew of awards, including the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Beloved and the 1977 National Book Critics Circle Award for Song of Solomon. In recognition of her contributions to writing and publishing, Morrison received the 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature, making her the first Black woman to be selected for the award. The Nobel committee noted in its citation that Morrison “who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality.”

In 2000, Morrison received the National Humanities Medal followed by a 2012 Presidential Medal of Freedom medal from Barack Obama. The National Book Critics Circle again celebrated the distinguished author in 2015 with its lifetime achievement award and today grants the Morrison Award in her honor. In 2016, she accepted the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction. Morrison received honorary degrees from almost every Ivy League university, as well as Oberlin College, Sarah Lawrence College, and the University of Michigan.

Both Sula and Beloved were finalists for the National Book Award. When Beloved wasn’t selected as the winner in 1987, it was seen as a major snubbed and prompted 48 Black writers and critics to protest the decision by signing a letter published in The New York Times Book Review. Among the heavyweight signatories were Maya Angelou, June Jordan, Houston A. Baker Jr., Lucille Clifton, Amiri Baraka, Angela Davis, Henry Louis Gates Jr., and Alice Walker.

Plays and Opera Librettos

Morrison explored art forms other than novels, most especially plays and opera librettos, the texts accompanying operatic music. She wrote her first play, Dreaming Emmett, in the mid-1980s. The work reimagined Emmett Till’s life, which had ended with the Black teenager’s brutal murder at the hands of several white men in 1955.

Morrison wrote the lyrics for “Four Songs” with composer Andre Previn in 1994 and “Sweet Talk” with composer Richard Danielpour in 1997. Her operetta, Margaret Garner, explored slavery through the true life story of one woman’s experiences. The work debuted at the New York City Opera in 2007.

Later, Morrison worked with opera director Peter Sellars and songwriter Rokia Traoré on a production inspired by William Shakespeare’s Othello. The trio focused on the relationship between Othello’s wife, Desdemona, and her African nurse, Barbary, in Desdemona, which premiered in London in the summer of 2012.

Marriage and Motherhood

While teaching at Howard University, Toni met Harold Morrison, an architect originally from Jamaica. The couple married in 1958, and Toni Wofford officially became Toni Morrison.

In 1961, Toni and Harold welcomed their first child, a son also named Harold but known by his middle name, Ford. The family spent the summer of 1963 traveling in Europe, after which Toni and Ford returned to the United States. Harold, however, moved back to Jamaica.

At the time of their separation, Toni was pregnant with the couple’s second child. She moved back home to live with her family in Ohio before the birth of her son Slade in 1964. Despite divorcing Harold that year, she kept her married name and raised the former couple’s sons as a single mother.

Ford became an architect like his father, while Slade became an artist. Toni and her younger son cowrote several children’s books in the late 1990s and 2000s. Slade died of pancreatic cancer in December 2010.

Death

Morrison died on August 5, 2019, from complications of pneumonia at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City. She was 88 years old.

That November, more than 3,000 people attended her public memorial service. Speakers at the event included authors Ta-Nehisi Coates, Jesmyn Ward, and Fran Lebowitz, as well as Angela Davis and Oprah, who recalled being very nervous when they first met in 1993. “My head and my heart were swirling,” the media mogul said. “Every time I looked at her I couldn’t even speak. I had to catch my breath.”

Prior to her death, Morrison was the subject of several documentaries, most notably Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am. The film released in June 2021. Additionally, her son Ford co-produced The Foreigner’s Home, a 2018 documentary about his mother’s guest-curated exhibit at the Louvre Museum in 2006 of the same name.

In 2023, the United States Post Office printed a stamp in her honor.

Quotes

- If there’s a book you really want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.

- Home is an idea rather than a place. It’s where you feel safe. Where you’re among people who are kind to you—they’re not after you; they don’t have to like you—but they’ll not hurt you. And if you’re in trouble they’ll help you… It’s community—that’s another word for what I’ve described.

- The ability of writers to imagine what is not the self, to familiarize the strange and mystify the familiar, is the test of their power.

- Everywhere, everywhere, children are the scorned people of the earth.

- When people say they don’t have time to write with small children, well, for me it was the opposite. I didn’t write anything before I had them. They gave me that.

- Love is or it ain’t. Thin love ain’t love at all.

- All the books that were being published by African American guys were saying “screw whitey,” or some variation of that. Not the scholars, but the pop books. And the other thing they said was, “You have to confront the oppressor.” I understand that. But you don’t have to look at the world through his eyes. I’m not a stereotype; I’m not somebody else’s version of who I am.

- There are women in the world who get divorced and that’s what they do. Their conversation is about it. He or she didn’t, or I used to, or therefore, and all of their emotions, all of their activity is about that one break-up. Why it happened, what was involved—they never move past it.

- The pop stuff—it’s—it’s so low. People used to stand around and watch lynchings. And clap and laugh and have picnics. And they used to watch hangings. We don’t do that anymore. But we do watch these other car crashes. Like those Housewives. Do you really think that your life is bigger, deeper, more profound because your life is on television? And they do.

- We are born already, and we are going to die. You really have to do something you respect in between.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Since 2010, Donna Raskin, a longtime writer and editor, has taught history classes at the College of New Jersey. As a child, she read and re-read every book in the Childhood of Famous Americans series. As an adult, she collects fashion history books and has traveled to Paris on a fashion history tour. In addition to contributing to Biography.com, she is the senior health and fitness editor at Bicycling and Runner’s World.