Key Takeaways:

- Philip “The Chicken Man” Testa rose to power in the Philadelphia mafia after Angelo Bruno’s assassination in 1980, ending an era of relative peace.

- Testa’s reign as mob boss was cut short in 1981 when a nail bomb killed him at his South Philadelphia home, sparking the violent Second Philadelphia Mob War—and Bruce Springsteen’s song, “Atlantic City”.

- The Philadelphia mob wars, as featured in Netflix’s Mob War: Philadelphia vs. The Mafia, escalated under Nicodemo “Little Nicky” Scarfo, whose paranoia and brutal tactics led to betrayals, federal indictments, and the mafia’s decline.

Bruce Springsteen’s songs are filled with colorful characters: There’s Blind Terry; Rosalita, who needs to jump a little higher; a Janey who shouldn’t lose her heart, and another Janey who needs a shooter; and more Marys than even the Bible mentions.

Perhaps the most unforgettable name in the Springsteen songbook comes from “Atlantic City,” which opens with the immortal lines: “Well, they blew up The Chicken Man in Philly last night / Now they blew up his house too.”

But “The Chicken Man” wasn’t just a character that Springsteen made up—he was real.

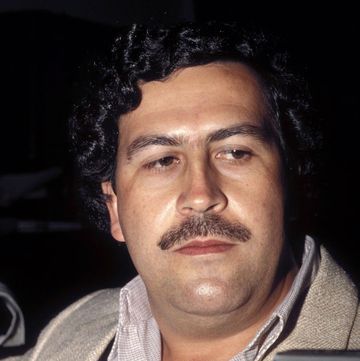

The nickname belonged to Philip Testa, a Philadelphia mob boss who was, in fact, blown up, and his ominous legacy still looms large over two major new releases out this week: Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, the new film that chronicles the making of Nebraska (the 1982 album that features “Atlantic City”), and Netflix’s new docuseries, Mob War: Philadelphia vs. The Mafia, which revisits the bloody turf war sparked, in no small part, by the Chicken Man’s explosive death.

Who was Philip Testa, a.k.a. “The Chicken Man”?

Philip “The Chicken Man” Testa was born on April 21, 1924. While most accounts describe him as the Philadelphia-born son of Sicilian immigrants who settled in South Philadelphia during the early 20th century, genealogical records and the National Crime Syndicate identify his birthplace instead as Mistretta, Sicily, suggesting he may have immigrated to the United States as a child. (As with many figures in organized crime, the truth is partly obscured by myth and rumor.)

Some suggest Testa got his “Chicken Man” nickname from his distinctly pock-marked face, a lifelong reminder of a childhood battle with chicken pox; others say it stems from Testa’s involvement in a legitimate poultry distribution business. But even if Testa’s primary occupation was poultry, that wasn’t where his proverbial bread was buttered.

How did Philip Testa come to power in the Philadelphia mafia?

Philip Testa built his reputation by climbing the ranks of Angelo Bruno’s Philadelphia crime family, eventually serving as Bruno’s underboss. Bruno, who was appointed by The Commission—the governing body that oversaw organized crime operations in the U.S.—took control of the Philadelphia mafia in 1959.

Known as “the Gentle Don,” Bruno preferred peaceful methods of conflict resolution over open violence, though he wasn’t above ordering hits when he felt they were necessary. Bruno’s focus on reliable, old-school rackets like gambling and protection helped him maintain power and keep law enforcement at bay.

But for as bloodless as Bruno’s reign was, his demise was as memorably brutal. On March 21, 1980, the 69-year-old Bruno shot in the head while seated in his car. The graphic images made their way to the newspapers, and a firestorm of speculation spread about who was behind the assassination.

Most signs pointed to Bruno’s own consigliere at the time, Antonio Caponigro, who reportedly believed he had the support of The Commission to kill Bruno and ascend to running the Philadelphia crime family. If that was what Caponigro believed, he was mistaken, and paid for it dearly. Weeks after Bruno’s killing, Caponigro’s body was found stripped and beaten in the trunk of a car in The Bronx.

After Bruno’s assassination, Testa was chosen to succeed his longtime boss. But the violent killing of “the Gentle Don” didn’t just end a relatively low-key era—it shattered the fragile peace that had held Philadelphia’s crime underworld together, leaving behind a power vacuum that “the Chicken Man” wasn’t prepared to fill.

How did “The Chicken Man” die, and who killed him?

Less than a year after taking over the Philadelphia crime family, Testa was killed by a planted nail bomb on the porch of his South Philadelphia home on March 15, 1981. The pre-dawn blast, which ripped through Testa’s house, was so forceful that neighbors initially thought a factory exploded.

The brazenness of the hit on Testa announced the end of the “Gentle Don”-era restraint in Philadelphia and made clear that in the City of Brotherly Love, power could be grabbed not just by slow, passive ascension, but by killing the man who held the crown.

The news of Testa’s shocking death immediately made headlines, and Springsteen reportedly followed the coverage as he wrote his bleak look at criminal life in “Atlantic City.”

In hindsight, Testa’s death wasn’t so much an end as it was an opening act of the so-called Second Philadelphia Mob War. Testa’s confessed assassin, Theodore DiPretoro, said he acted with the help of Rocco Marinucci, and that the boss’s murder was less about individual vengeance and more about a widening power vacuum.

What happened in Philadelphia’s mob wars after Philip Testa’s death?

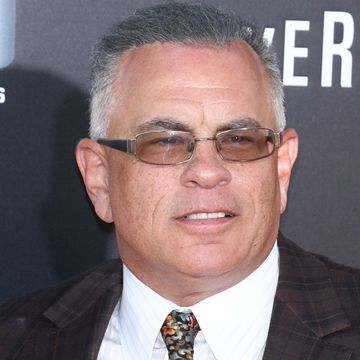

Testa’s consigliere, Nicodemo “Little Nicky” Scarfo, ascended to the position of boss and oversaw the Philadelphia crime family from 1981 to 1990. During that time, Testa’s son, Salvatore, also rose through the city’s mafia ranks, which reportedly made Scarfo paranoid. In 1984, Scarfo ordered the murder of Salvatore Testa, who was shot and killed in New Jersey less than four years after his father’s explosive death.

While the hit on Salvatore Testa may have strengthened Scarfo’s grip on power in the short term, it damaged his standing in the underworld. The killing eroded his crew’s loyalty, and when federal prosecutors charged Scarfo and 16 associates with racketeering, extortion, and murder in late 1988, several family members flipped and cooperated with the FBI.

When Scarfo fell from power, a new vacuum opened in the Philadelphia mafia. Giovanni “John” Stanfa took control of the crime family, hoping to restore order and stability.

The Netflix series Mob War: Philadelphia vs. The Mafia picks up the story here, following Stanfa’s attempts to calm the chaos while two ambitious younger mobsters—Joseph “Skinny Joey” Merlino and Ralph Natale (the son of longtime Philadelphia mob figure Michael Natale)—watched from the sidelines, ready to seize their chance for a bloody rise.

Where can I watch Netflix’s Mob War: Philadelphia vs. The Mafia?

The entire series is now available to stream on Netflix.

Stream Mob War: Philadelphia vs. The Mafia here.

Michale Natale is a News Editor for the Hearst Enthusiast Group. As a writer and researcher, he has produced written and audio-visual content for more than fifteen years, spanning historical periods from the dawn of early man to the Golden Age of Hollywood. His stories for the Enthusiast Group have involved coordinating with organizations like the National Parks Service and the Secret Service, and travelling to notable historical sites and archaeological digs, from excavations of America’ earliest colonies to the former homes of Edgar Allan Poe.