Key Takeaways:

- John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865.

- Booth was part of a nine-person conspiracy that also planned to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward. Both men survived.

- Five of the conspirators were killed, and the four others served prison time.

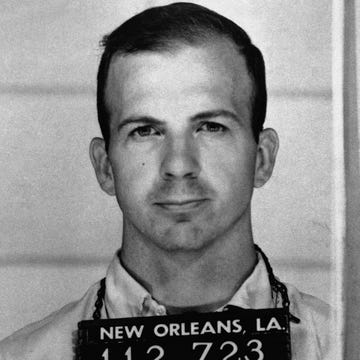

Nearly everyone knows that on April 14, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was shot and killed in Ford’s Theatre in Washington by actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. But what many might not realize is that while Booth was the man who pulled the trigger, he didn’t act alone. Moreover, the murder of a president wasn’t the only bloody deed Booth hoped would occur that night.

To say that there was a “conspiracy” involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln isn’t to suggest there is a secret alternative to the official story in the way conspiracy theories crop up after modern high-profile killings. Rather, in the wake of Lincoln’s death, investigators uncovered that a group of conspirators were involved in the plot to kill the president and had planned to kill other high-profile politicians as well.

The official record shows nine people colluded with Booth. Others were questioned and released due to lack of evidence, but these nine either helped plan the nefarious deeds, abetted Booth’s escape, or took action that night to attack the United States. Four of these conspirators were sentenced to death for their crimes, including the first woman ever executed by the federal government.

Kidnappings and the Knights of the Golden Circle

Booth’s plotting against Lincoln began before the Civil War was even over. Originally, he didn’t think about killing the president. He wanted to kidnap him, and Booth wasn’t the only one with such designs in mind.

In 1860, the Maryland native joined a “secret society” known as the Knights of the Golden Circle. This pro-slavery—and therefore pro-Confederate—organization was founded in 1854 during the Franklin Pierce administration. Its original intention was to promote the annexation of territories south of the border, including Mexico and Cuba, that would allow for the formation a “golden circle” of new slave states. Golden Circle members believed this would ensure permanent economic and political power in the face of a growing abolitionist movement. (It should be noted, however, that Pierce was pointedly not an abolitionist.)

When abolitionist sentiments within the nation were further enflamed by the controversial Dred Scott decision at the beginning of President James Buchanan’s term, the Knights of the Golden Circle shifted their focus toward the idea of succession for the southern states. (Allegedly, some members of Buchanan’s cabinet were Knights of the Golden Circle, which helped spread the sentiment.) The election of Lincoln, in their eyes, made secession inevitable. Unless, of course, Lincoln wasn’t sworn into office.

In a brash and treasonous act, the Knights of the Golden Circle concocted the Baltimore Plot, which sought to intercept President-elect Lincoln in a kidnapping and prevent his inauguration. As Dorothea Dix, a nurse who overheard the plot and reported it to the authorities, summarized, “Mr. Lincoln’s inauguration was thus to be prevented, or his life to fall a sacrifice.” Although the Baltimore Plot was foiled, thanks to the efforts of detective Allan Pinkerton and others, the idea of kidnapping Lincoln lingered in the minds of two Knights of the Golden Circle members: John Surratt Jr. and John Wilkes Booth.

Although Booth was the one who pulled the trigger, and is often credited with concocting the plans, it’s not unreasonable to wonder if any of what transpired would have unfolded without Surratt. While Booth, as an actor, made for a charismatic leader to rally around, Surratt had the connections. A college-educated man of some means, Surratt used his position as a U.S. postmaster to work covertly as a spy for the Confederacy. He shepherded messages across Union lines and conferred with Confederate Secret Service agents in Canada.

The National Parks Service credits Surratt with bringing young David Herold and German boatman George Atzerodt into the fold of the conspiracy, as well as introducing disaffected Confederate veteran Lewis Powell “into Booth’s orbit.” Another key player connected to Surratt in the eventual plot was his mother, Mary Elizabeth Surratt, whose Washington boarding house was where the conspirators met. President Andrew Johnson later referred to this site as “the nest that hatched the egg.” Booth attempted to round out the clique of conspirators with two childhood friends, Samuel Bland Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen. (Dr. Samuel Mudd, who may have introduced Surratt and Booth, also may have been involved early on.)

Originally, the group assembled to discuss how to kidnap Lincoln and blackmail the Union so that wartime prisoner exchanges between the Union and the Confederacy would resume. In July 1863, President Lincoln had halted such swaps after Confederate President Jefferson Davis began preventing Black soldiers from being part of exchanges in 1862. Lincoln refused to resume the prisoner swaps until race wasn’t a factor.

Arnold reportedly walked away before any plot could be put into action, according to the NPS, “following an argument in which he told Booth that his kidnapping plans were impractical.” Impractical as it might have been, Booth and his cadre attempted to execute their plan on March 17, 1865, only to be foiled when the president changed his intended theater plans at the last minute. Less than a month later, the Confederacy surrendered, ending the Civil War entirely.

This should have put an end to the Confederate sympathizers’ plotting. At the very least, it did for O’Laughlen, who reportedly left the conspiracy after the failed kidnapping plot and had no knowledge of what came after. But for Booth and his co-conspirators who remained, the cause wasn’t over—the intention had just changed. It wasn’t enough to kidnap the president. The plan, instead, would be to behead the Union serpent entirely.

The Assassination Plot

The plan for the night of April 14, 1865, was three-pronged: John Wilkes Booth would access the Presidential Box at Ford’s Theatre and shoot the president during a particularly raucous scene of the play Our American Cousin. Meanwhile, Atzerodt would kill Vice President Andrew Johnson, who was at the Kirkwood Hotel. Lewis Powell— guided by Herold, who knew the area better—would make his way into the home of Secretary of State William Seward and murder him, after which Herold was to rendezvous with Booth in Maryland.

Booth’s part of the plot went largely according to plan, with the exception of a leap from the Presidential Box to the stage below, which might have been how Booth’s leg wound up injured. Booth had even roped in an unsuspecting stagehand named Edman Spangler to hold a horse for him at the back of the theatre so he could make his escape. Booth and Herold made their way to the home of Mudd, who repaired Booth’s leg with a splint and gave them a space to rest. The duo then went to the Richard Garrett farm in Virginia, where Herold surrendered and Booth was gunned down.

Atzerodt, however, couldn’t go through with his part of the plot. He reportedly lost his nerve when he arrived at the hotel where Johnson was staying. Atzerodt instead opted for drinks at the hotel’s bar and wandered out into the grim April night. He was arrested several days later.

For his part, Powell likely believed he had completed the task. He had infiltrated the Seward home in Lafayette Square and, armed with a revolver and a Bowie knife, attacked Secretary Seward, his son Frederick, and maître d’ William Bell. However, the victims survived. After Powell’s revolver misfired, he attempted to slash the elder Seward’s throat. But the secretary was wearing a splint to fix a broken jaw that ultimately protected him from a fatal knife wound. Powell fled the house and, three days later, arrived at the Surratt boarding house, where he was arrested.

John Surratt was pointedly not involved in the plot itself. At the time of the assassination, he was in New York, investigating a prisoner-of-war camp. When word of the slaying reached him, he fled to Canada, eventually adopting an alias and taking work as part of the Papal Guards at the Vatican.

What Happened to the Lincoln Conspirators

After their arrests, the men with direct involvement in the plot—Atzerodt, Herold, and Powell—were grouped with the people attached to the conspiracy in other ways, from abettors like Spangler and Mudd to the men aware of the earlier kidnapping plot, O’Laughlen and Arnold. Both for her role in hosting the plotters gatherings, and perhaps also as a stand-in for her son, Mary Surratt rounded out the group of eight.

The eight were tried before a military tribunal (a controversial choice, but undertaken as they were deemed “enemy combatants” during a time where Washington, D.C., was still under martial law). All were found guilty.

Spangler was sentenced to six years in prison. Arnold, O’Laughlen, and Mudd were given life in prison. President Johnson later pardoned Arnold and Mudd, while O’Laughlen died of a yellow fever outbreak in the prison before his crimes could also be forgiven. While still behind bars, Mudd actually helped combat the yellow fever outbreak and saved many lives in the process.

Powell, Herold, Atzerodt, and, most controversially, Mary Surratt, were all sentenced to death by hanging. After the sentencing, members of the tribunal penned a letter to the president asking for clemency for Mary, given her age, her gender, and her lesser involvement in the crime. Johnson did not acquiesce, and she became the first woman ever to be executed by the federal government.

By the time John Surratt was found in Egypt in 1866 and extradited to the United States, he only faced a civil court, which ended in a hung jury. He was set free, facing no punishment for his involvement. After years spent in hiding from the consequences of his conspiracy, he took to the spotlight by launching a lecture tour about his role in the kidnapping plot. However, the tour was cancelled due to public outcry.

Surratt lived until 1916, more than 50 years after his mother was executed. By the time Surratt, the last of the Lincoln conspirators, died, two more presidents had been assassinated—James Garfield and William McKinley—and the son of a former Confederate chaplain, Woodrow Wilson, had ascended to the highest office in the nation.

Michale Natale is a News Editor for the Hearst Enthusiast Group. As a writer and researcher, he has produced written and audio-visual content for more than fifteen years, spanning historical periods from the dawn of early man to the Golden Age of Hollywood. His stories for the Enthusiast Group have involved coordinating with organizations like the National Parks Service and the Secret Service, and travelling to notable historical sites and archaeological digs, from excavations of America’ earliest colonies to the former homes of Edgar Allan Poe.